Buildings for

the future

Steiner AG constructed its first building in 1947. Since then over 1,200 residential buildings, 540 commercial properties, 45 hotels and 150 infrastructure facilities have been developed, built or renovated by Steiner. We would like to present 0.75 per cent of these structures to you here.

As Karl Steiner is supervising work on the interior of the Zurich Congress Centre in 1939 at the age of 28, he thinks to himself, “I can do more than this. I could oversee the construction of an entire high-rise, offering guaranteed prices and completion dates.” When a property goes up for sale in 1946 on Talstrasse, not far from Paradeplatz, he and a partner jump at the chance.

Both of the villas present there are demolished and replaced by a 20-metre high perimeter block. Steiner takes care to use quality materials and to execute all work with precision. Shops with display windows can soon be seen between the pillars of local Solothurn limestone. There are offices on the five floors above, which maintain the window line from below.

Karl Steiner takes a big risk. Building costs amount to CHF 115 per cubic metre. The risk increases when the partner decides to leave and must be compensated for his investment. But when the building is finally finished, Steiner is able to lease it out immediately. He even receives the city of Zurich’s Outstanding Building Award.

The building still belongs to the Steiner family today – and it is just as popular with tenants. In 2014, the famous interior designer Alfredo Häberli designed avant-garde retail premises in it for a menswear brand.

A steel scaffold still envelops the Solothurn sand lime brick masonry.

View of Talstrasse/corner of Pelikanstrasse: The building lines permitted a height of 20 m on Talstrasse, 16 m on Pelikanstrasse.

On 30 November 1960 there is no more urgent item on the agenda in the Zurich Parliament than whether the city of Zurich can rent an administrative building from a private company. Until then, the city had always built its own buildings. Due to the acute shortage of space, however, the city council proposes to rent the still-to-be-built building in Parkring 4 from Steiner AG. The rent would be low, CHF 70 per square metre, which can be explained by the fact that “the general contractor was able to award the work economically”, as the Schweizerische Bauzeitung trade journal puts it. After a heated discussion, Parliament passes the law, 54 votes to 52.

On 21 January 1963 the Department of Education moves into the new building and pays a rent of CHF 321,540 per year. As a comparison: the city of Zurich currently pays CHF 26 million in rent per year for office space.

In 1953, Max Frisch, himself a qualified architect, wrote that Swiss architecture has “a cute, twee quality almost everywhere”. This cannot be said about the administrative building, which introduces a modernist element to the homely Enge district – if for no other reason than because of its daring “System K. Steiner” grid facade, a construction that features aluminium, wood-framed windows and glass elements covered with blue film. In 1966, the city buys the building, which has been listed since 2005.

Typical 1960s: prefabricated grid pattern façade “System K. Steiner” in wood, aluminium and glass.

Simply beautiful: the stairwell from which two corridors lead off per floor.

Swissair grows and grows. Between 1946 and 1966, it increases its passenger numbers 40-fold from an annual 60,000 to 2.4 million. Aircraft after aircraft is purchased. The Zurich Hirschengraben head office is bursting at the seams.

In 1959, Swissair commissions Steiner AG with finding land for a new building. Steiner finds it in Balsberg, and the only problem is that the 50,000-square-metre plot is divided between two communities: Opfikon and Kloten. Steiner skilfully brings both parties on board. Planning permission follows in 1963.

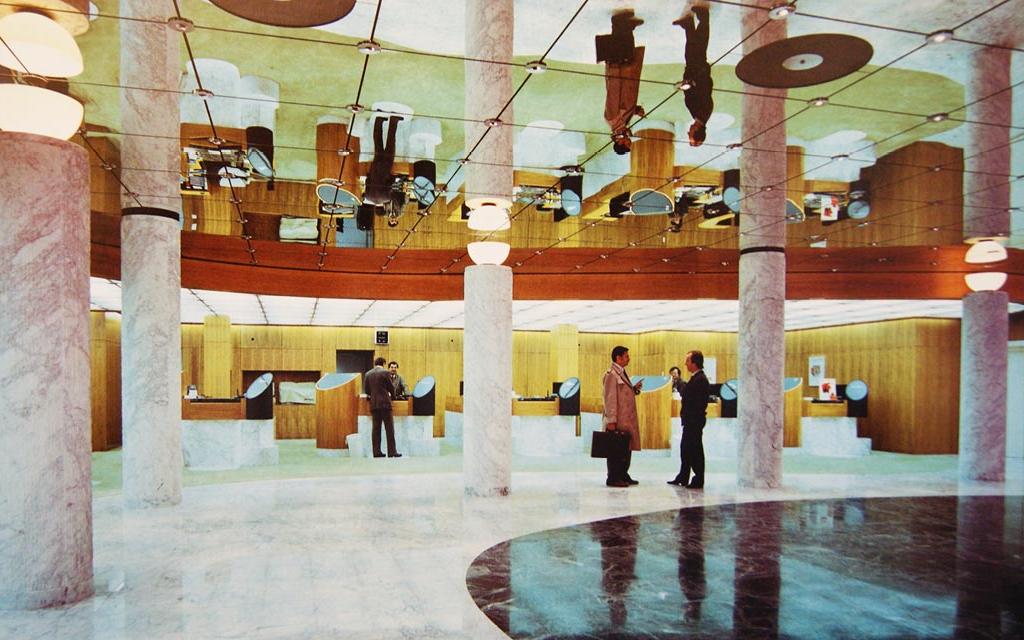

The head office becomes a milestone in the history of Steiner, something that can be ascribed not only to the reputation of the customer, but also to the building itself: its atrium and windows recall modern American architecture. It was designed by Steiner’s own architectural department – Zurich’s largest architectural “firm” at the time. Incidentally, an apprentice designer of high-rise buildings was particularly enthusiastic at the drawing board: Peter Steiner, the 18-year-old son of the boss.

The “Balsberg” has excellent traffic connections on the national road between Zurich-Oerlikon and Kloten airport.

The car park shell. 670 cars will be able to park here.

In 1965, the first computer arrives at Steiner. The market leader in this sector is IBM. Without an IBM computer, NASA would have had trouble getting to the moon in 1969. The fact that Steiner can build the global company’s Swiss head office is not only an accolade, but also the beginning of a decade-long partnership.

This site is one of the most valuable in Zurich: an empty space between buildings on General-Guisan-Quai, freed up by the demolition of the Palais Henneberg. IBM chooses Zurich’s best master builder as its architect: Prof. Jacques Schader. In 1969, he made a splash on the international scene not far from General-Guisan-Quai with the Freudenberg schoolhouse. Now he designs one of Zurich’s finest office buildings.

A grid facade made of glass and anodised metal covers the structure’s different elements. All the building has in common with the neighbouring historical structures is its size, since Schader does not go in for the ornamental. For him, utility, durability and classical beauty are more important – virtues that point to Schader’s original background as a craftsman. Like Karl Steiner, the master architect entered the world of high-rise buildings through the door of interior design.

With the new IBM head office, modern design takes up a prominent place in Zurich.

Computer centre in the IBM building.

What to do with all these students? Back in the 1960s, debates rage about expanding the University of Zurich. Right in the middle of the debate is Karl Steiner, to whom Zurich’s Government Council awards the contract to plan the expansion in 1961. In 1965, he publishes a study entitled “Problems of University Expansion” at his own expense. As a member of the canton’s planning commission, he now proposes a new campus on the Strickhof site.

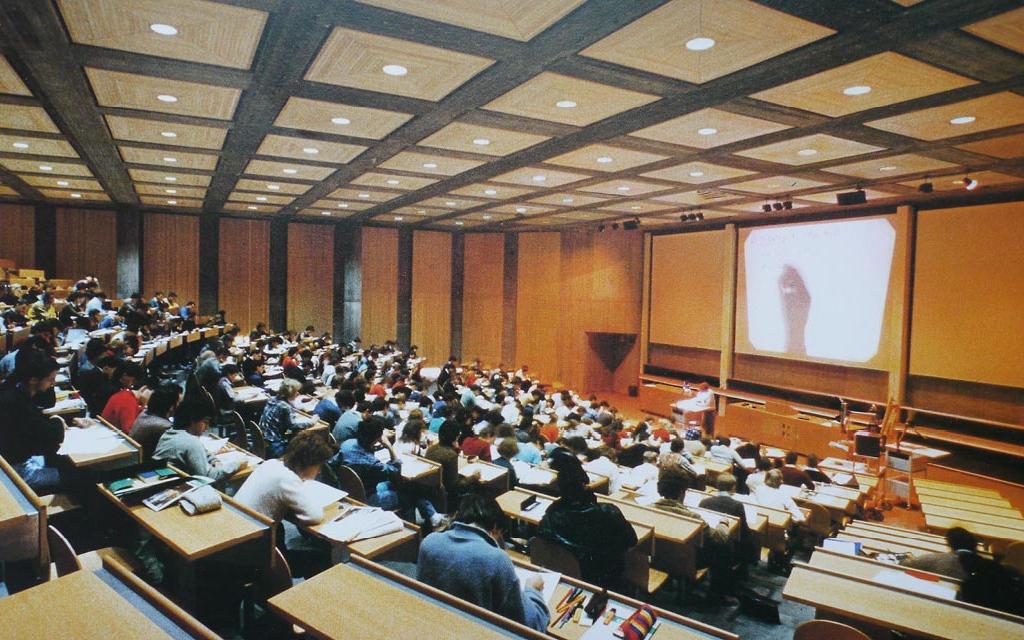

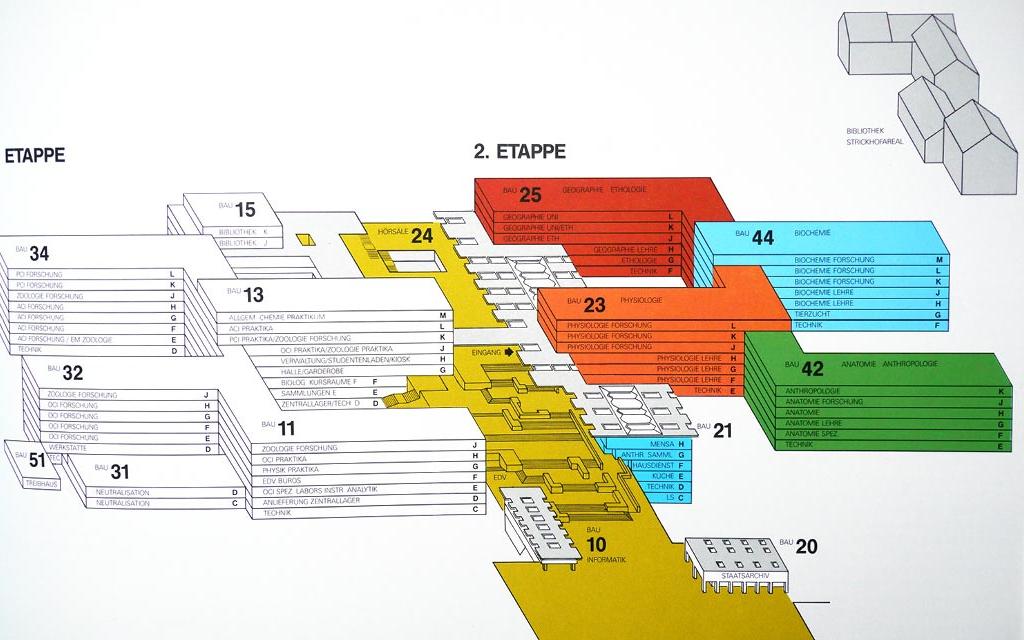

No sooner said than done. In 1971, voters approve funding of over CHF 600 million. Two years later, the first building phase begins. Steiner is responsible for the laboratory buildings and is not commissioned as the general contractor until the second stage of development. Finally, Steiner is able to take up the proposals from the 1965 study: flexible multi-purpose lecture rooms that can increase utilisation levels, pragmatic architecture, prefabricated concrete elements and standardised interior fittings – the latter from Steiner, of course.

The opening takes place in 1983. Steiner AG’s commitment to building universities continues. In 1997, it manages Switzerland’s largest construction project, the third phase of ETH Zurich’s Hönggerberg campus. In 2015, it also renovates the HPM building at Hönggerberg and adds another floor.

Large auditorium with air conditioning and the latest technology.

Colour markings: the building in the 2nd construction phase.

Resembling a gigantic reptile, the Quai du Seujet nuzzles the banks of the Rhone. Apartments, offices, shops, restaurants and a school come together to form a single “megastructure”, as described by the architecture theorist Reyner Banham in 1979. The building, over 300 metres long, is a 15-floor “city in the city”. It represents an antithesis to Le Lignon and other structures shooting up like mushrooms in the 1960s and 1970s throughout Switzerland, buildings that are causing people to start moving away from urban areas.

The Quai du Seujet is gigantic, yet not indiscriminate. The structure’s topography makes it possible to include walkways and open terraces on the fifth floor, which provide a wonderful view of the old town. To ensure the fine view remains accessible to the inhabitants of adjoining Saint-Jean, the architects reduce the height of the structure in the middle. The 99 apartments at Quai du Seujet also boast a panoramic view and their unusual layout is surprising: the dining room stands at a 45-degree angle to the façade, providing novel perspectives and spatial possibilities.

Quai du Seujet at the beginning of the 20th century.

Construction site on the banks of the Rhone: High-rise building now follows civil engineering and foundation work.

Noble materials for interior fittings on the ground floor of the Quai du Seujet.

Procter & Gamble has been conquering new markets in Europe, the Middle East and Africa from its Geneva headquarters since 1956. The US-based corporation has been so successful that it has become the third largest private employer in the canton of Geneva. In contrast, Steiner is still a small player in Geneva. The Zurich company has had a subsidiary there only since 1979.

It is therefore all the more satisfying when Steiner submits the successful bid for the construction of the prestigious new Procter & Gamble Swiss head office in 1983.

Based on Bernard Erbeia’s plans, Steiner build a high-rise with nine floors on a three-floor base. Steiner’s highly acclaimed facade of insulated glass windows is interrupted only by thin aluminium profiles. It acts like a mirror reflecting its environment: international Geneva. The interior – in keeping with the “American way of life” – is fully air-conditioned.

The 550 employees are able to move into their new offices in 1985, one month earlier than scheduled.

Thirty years later the building is transformed into the Nations Business Center – again by Steiner, but this time by the Conversion and Renovation department.

Mirror, mirror on the skyline - staff restaurant in front of the glass façade.

Historically one of Steiner's strengths: laboratory buildings. Here nappies undergoing a stress test.

When Karl Steiner bought a total of 17 properties in the 1970s in Zurich’s old town, he fortunately didn’t realise how much of an adventure he was embarking upon. Originally, he wanted to demolish the old buildings and replace them with modern offices. But the listing as a historic site and the city’s new housing ordinance threw a spanner in the works.

After years of going back and forth, a smart idea brings momentum to the situation: a hotel also provides housing, if only temporarily! In 1990, building begins based on plans by architect Tilla Theus.

Muscle power and inventiveness are required at the compact construction site. There are no turnkey solutions for upgrading the often dilapidated, historic buildings. In 1995, the Hotel Widder opens its doors. The walls dating back to the Middle Ages house 49 rooms, each one different and boasting extensively restored murals and other historic features. Visitors enjoy an intimate encounter with Zurich’s urban history.

Site inspection (LtoR): Thomas Grossenbacher and Dr Robert Holzach from the promoter (SBC, now UBS) with architect Tilla Theus and Peter Steiner.

How do you get a 32-m-long steel girder through a listed façade?

A visionary idea, a unique hotel: 5-star luxury within medieval walls.

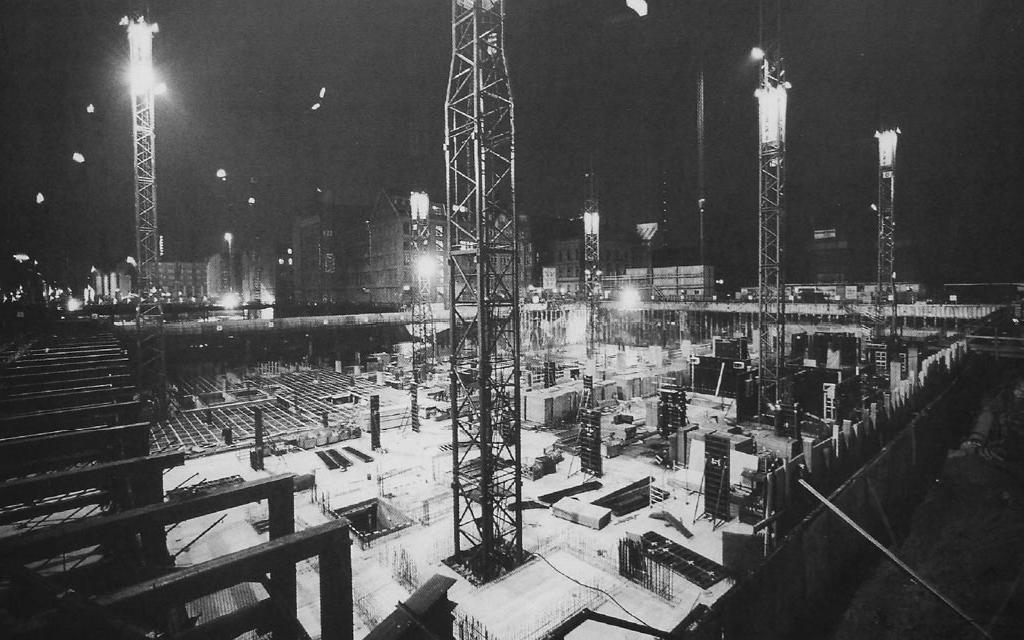

Following reunification, thousands of tourists visit Berlin’s historical centre, the Gendarmenmarkt. At the end of 1993, the first thing they saw, however, was not the Schinkelsches Theatre, but Europe’s largest urban excavation: a 20,000-square-metre hole, with 10 construction cranes rising above it.

Back in 1987, the East German government started building a warehouse on Friedrichstrasse, but work stopped when money for the project ran out. Now the location is home to Friedrichstadt-Passagen: three apartment and office blocks and a shopping mall. The architects involved in one block read like an architectural “Who’s Who”: Nouvel, Cobb, Ungers. Ungers designs the largest block adjoining the Gendarmenmarkt. In contrast to Nouvel’s expressive glass construction, Ungers’ structure recalls a traditional Berlin design from the Wilhelminian period.

The general contractor is Steiner Infratec, whose establishment in 1990 heralded the start of Steiner AG’s internationalisation. The cooperation with Ungers was so successful that Steiner Infratec also builds the Basler Versicherungen headquarters with him in Cologne a short time later.

Time is money: Floodlights allow work to continue on Europe's largest construction site.

The Nestlé headquarters “En Bergère” in Vevey are not only the centre of a global corporation, but also of global architecture. In 1960, Jean Tschumi created what was then western Switzerland’s largest office building: a house perched on pillars, beyond time and space.

The building itself never ages, only its underlying technology. In the middle of the 1990s, inevitably, it is time to do something about it. In 1996, the plans arrive from Lausanne-based architects Richter & Dahl Rocha. The complete renovation is expected to take three years, during which the work done by 1,700 Nestlé employees cannot be affected. Perfect construction management is required – something guaranteed by Steiner AG.

In addition, the architects want to create a lightwell in the middle of the Y-shaped building, to enhance the Escalier Chambord, the building’s famous stairway. A change that will compromise the architecture? Not really. Tschumi himself had planned the lightwell, but was unable to execute it for technical reasons. Using a helicopter, Steiner lowers the new element – which looks like a “lamp shade” and is made of composite materials – onto the roof.

Geometrically a Y, architecturally an exclamation mark. Jean Tschumi's Nestlé head office “En Bergère” from 1960.

In the 1990s, the rich Gulf states entered a competition that had once gripped Paris and New York: a global race to build the highest building in the city, the country, the world. What a contrast to Steiner’s idyllic home town of Zurich, where the construction of high-rise buildings has been prohibited since 1984. And that’s a shame, since, in 1972, Steiner built Zurich’s tallest building at the time, the 85-metre Hotel International.

Steiner is now building at very different altitudes in Dubai instead. The company receives access to this market through its 1992 joint venture, Turner Steiner International (TSI), since Turner has an excellent network in the Middle East.

The joint venture culminates with the construction of the Emirates Towers. At 355 and 315 metres, the towers designed by the NORR architectural firm remain the highest buildings in the emirate for nearly a decade. They are still the highest Steiner has been involved in to date. The larger structure serves as an office building, the smaller is a luxury hotel.

The 2000 opening marks both the high and end point of the TSI joint venture. Hochtief, the German construction group, acquires Turner the same year.

The Emirates Towers are home to the luxurious shopping centre The Boulevard.

The Emirates Towers are still eye-catchers on Dubai's skyline.

There is nothing strange about resistance to planning permission. The ten years the city of Zurich and then City Councillor Ursula Koch have spent blocking planning permission are, fortunately, an exception.

To take a look back, in the 1980s Steiner was planning an office complex, Utopark, on the former Sihlpapier AG premises to the south of Zurich. When the city refused planning permission, a lengthy lawsuit began. Steiner finally won the case in front of the Federal Court in 1999.

Since then, however, times have changed and a development offering only offices is no longer required. Together with architect Theo Hotz, Steiner develops a new vision: a completely new type of shopping and entertainment centre, a “city in the city”. And this time it works. Planning permission is given in record time, the foundations are laid in 2004, the opening takes place in 2007. Every day since then, some 21,000 people have visited the 80 shops and 14 cafes and restaurants, as well as the cinema, cultural centre, church, library, gym, hotel, medical clinic and Kalander Square.

In 2013, Sihlcity even receives the Outstanding Building Award from the city of Zurich. In other words, good things come to those who wait.

The chimney, paper store and preparations centre from the former paper mill have been saved from demolition.

Kalanderplatz in the centre of Sihlcity.

Impressive architecture from Theo Hotz in the shopping centre.

The new millennium also awoke a new, urban spirit in Zurich. In 2001, the Zurich Tourist Office launches the new tagline “Zurich – Downtown Switzerland” and architects Gigon/Guyer deliver the architectural response: the Prime Tower.

At 126 metres, it is Switzerland’s tallest building. It is not outstanding for that reason alone, however. It makes clever use of perspectives and proportions: depending on your viewpoint, the tower resembles a slim silhouette or a broad torso. Another peculiarity: the high-rise seems to get broader towards the top, thanks to its overhanging elements. This structural reversal provides a larger surface area and greater stability.

Construction is jointly managed by Steiner AG and Losinger Marazzi AG. Inventiveness is called for with the formwork. It is not possible to attach scaffolding, so the decision is taken to use a climbing formwork. Floor by floor, the hydraulic shield slides upwards – all the way to the top.

The Prime Tower boasts a restaurant with a Michelin star and a bar, both open to the public. The Prime Tower is not an insular office building: it is representative of Zurich, which has become one of the world’s finest cities to live in over the last 15 years.

Overhangs give Prime Tower its chunky look.

The Prime Tower has excellent traffic connections from Hardbrücke station. On the left in the background, the four Hardau high-rise buildings.

If someone had looked for Lavasa on a map 15 years ago, they wouldn’t have found it. The city only existed in the mind of Ajit Gulabchand, chairman and managing director of the Hindustan Construction Company (HCC). Today Lavasa lies almost exactly 120 kilometres to the south of Mumbai and 50 kilometres to the east of Pune in the western state of Maharashtra.

Lavasa is admittedly far from complete. Four districts should someday make up this “Hill City”, in which 200,000 people will live and work. The first district, Davse, is taking shape. In 2009, the Lavasa Hotel School opened its doors, an offshoot of the famous Lausanne Hotel School. Moreover, the congress centre is fully booked.

If the undertaking proves to be a success, many more future “Lavasas” could alleviate the pressure India’s mega-cities are feeling. India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi wants to commission the construction of 100 new planned cities over the next 30 years. The market exists, but India has a shortage of know-how in of the areas of urban construction and construction management. That is one of the reasons HCC acquired Steiner AG in 2010 and made its subsidiary Steiner India Ltd. responsible for further development and construction of Lavasa in 2013. The cost of the project: CHF 1.4 billion.

Lavasa is a challenge, thanks to monsoons, changing political configurations, insufficient skilled labourers and sudden interruptions to construction work. But as the old Frank Sinatra song goes: if you can make it here, you can make it anywhere.

A touch of Italy in India - the lakefront promenade of Davse.

Lavasa City is on a tributary of the River Mutha.

The six structures next to the railway tracks seem to open like giant petals. The House of Peace is an architectural milestone – and more. It’s a prime example of the detailed planning and precise work carried out by the general contractor: Steiner AG.

This construction project is one of rare complexity. In order to secure the foundations in soft soil, Steiner needs to drive 300 piles up to 20 metres into the ground. They then become the resting place for the six ellipsoidal structures, in which not a single right angle can be found. This in turn means that geometry is a key concern on the construction site: wherever there are no building axes, the x and y coordinates have to be measured continuously. Tolerance is 6 millimetres.

The result is a building with a unique aura, precisely because of its complexity and transparency. The client is the famous Geneva Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies. Not so coincidentally, the structure’s complexity reflects the institute’s demanding mission: creating peace on Earth.

Train connection included: the Maison de la Paix also enjoys excellent traffic connections.

Without corners and edges - the six structures remind us of lotus leaves.

Streams of business people come out of the Oerlikon railway station heading for Hagenholzstrasse every morning. Where industry once flourished, office buildings now stand.

The latest example is SkyKey, the superlative high-rise developed and built by Steiner. A total of 42,000 square metres of office space and 2,500 offices (500 more than in the Prime Tower) are packed into the impressive Theo Hotz architecture and have been awarded the highest ecological certificate, LEED Platinum. The toilets, for example, are flushed using rainwater from the roof.

The sole tenant is Zürich Versicherungs-Gesellschaft AG, since SkyKey is the company’s new headquarters. The building is one in a long series of head offices that Steiner has built for international corporations like Swissair, IBM, Philips, Procter & Gamble, Swiss RE and Unisys.

With the construction of SkyKey, Steiner AG has filled the last gap at its former business location. Karl Steiner moved there in 1948; 15 years ago the industrial site was redeveloped into housing and space for service industries. Steiner has played a key role at Leutschenbach, the second largest development area in the city of Zurich. With that, SkyKey is both a key to the past and to the future.

Where now the high-rise office building, SkyKey dominates, this was the location for the Steiner AG head office until 2011.

Steiner AG has constructed for numerous international companies. The sole tenant of SkyKey is Zürich Versicherungs-Gesellschaft AG.

Everyone is welcome – except for car drivers. After all, the cooperative building society “mehr als wohnen” has set high ecological targets with its 2,000-watt-compliant structure. A tour of the nearly 400 apartments confirms this.

Steiner began construction of the housing development in 2012. The property directly borders the former Steiner factory site in Zurich-Oerlikon and is part of the second largest development area in the city of Zurich: Leutschenbach.

Five architectural offices have collaborated on this construction project. The residential designs are correspondingly diverse, ranging from traditional 2-to-6-room flats to innovative “satellite apartments”. The latter have a so-called flat-in-flat layout and, at 250 square metres, offer up to 10 rooms with individual wet rooms and communal kitchen and eating areas – ideal as a home shared by multiple generations. Office and retail units on the ground floor, green areas between the buildings and numerous common rooms all emphasise the new “mehr als wohnen” development concept.

On the central squares between the buildings, there is to be space for community.

The first residential units are nearly complete.